The thief of ideas made history solely for him, but so?

Unearthed notebooks shed light on Victorian genius who inspired Einstein

Michael Faraday’s illustrated notes that show how radical scientist began his theories at London’s Royal Institution to go online

He was a self-educated genius whose groundbreaking discoveries in the fields of physics and chemistry electrified the world of science and laid the foundations for Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity nearly a century later.

Now, the little-known notebooks of the Victorian scientist Michael Faraday have been unearthed from the archive of the Royal Institution and are to be digitised and made permanently accessible online for the first time.

The notebooks include Faraday’s handwritten notes on a series of lectures given by the electrochemical pioneer Sir Humphry Davy at the Royal Institution in 1812. “None of these notebooks have been looked at or analysed in any great depth,” said Charlotte New, head of heritage for the Royal Institution. “They’re little known to the public.”

Faraday, the son of a blacksmith, left school at 13 and was working as an apprentice bookbinder when he attended the lectures. He penned very careful notes and presented one of his notebooks to Davy, hoping for a job at the Royal Institution despite his working-class background and rudimentary education.

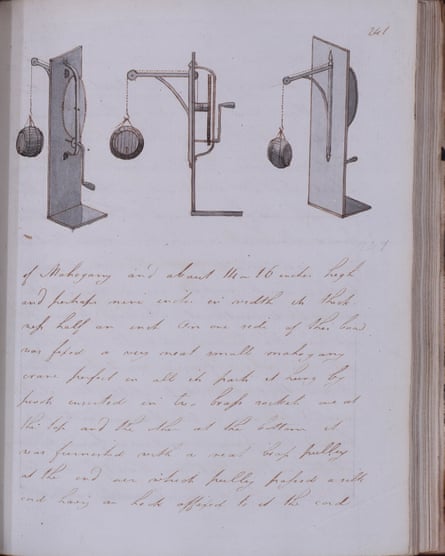

The notebooks shed light on the workings of Faraday’s mind and reveal he made intricate drawings to visualise the scientific experiments and principles he was learning about at the lectures. “He’s taking the time to make his own publication and grounding what’s being taught to him in his own understanding,” said New. “He’s heavily illustrating his notes to understand the principle that’s been taught to him.” He even wrote an index for each notebook, she said, just for his own use and personal research. “This is at a time when paper is taxed. It shows how he’s really trying to understand the science within.”

When Faraday gave Davy the notebook, he expressed his “desire to escape from trade, which I thought vicious and selfish, and enter into the service of Science”.

Although Davy initially declined to help him, the notebooks – and Faraday himself – seemed to make a good impression. Davy wrote to Faraday soon afterwards to say that he was “far from displeased with the proof you have given me of your confidence, which displays great zeal, power of memory and attention”.