风萧萧_Frank

以文会友世界秩序:重复运动的全球万花筒

https://chasfreeman.net/world-orders-the-global-kaleidscope-in-repeated-motion/

查斯·弗里曼 2022-09

外交和政策过程课程讲座

Chas W. Freeman, Jr. 大使(USFS,退役)

布朗大学沃森国际与公共事务研究所访问学者

2022 年 9 月 21 日来自华盛顿特区的视频

世界现在正处于向其组成区域和职能部门的新秩序的混乱过渡。 这并不罕见。 自从全球各地相互交流以来的五个世纪里,发生了许多这样的演变。

第一个相对于区域秩序的全球秩序直到 15 世纪最后几年才出现。 1492年,哥伦布横渡大西洋。 这将美洲与欧洲连接起来。 不久之后,即 1498 年,瓦斯科·达伽马环绕非洲到达印度。 这两件事首次使世界各大洲和海洋成为一个单一的地缘政治和地缘经济竞争场。 他们还开启了一个长达四个世纪的时期,欧洲技术、工业和军事能力的快速发展击败了所有竞争对手,西方帝国主义、殖民主义和思想征服了全球。

16世纪和17世纪,欧洲人消灭了美洲大部分土著居民,成为那里的主要人口,并开始将数百万被奴役的非洲人运往大西洋彼岸。 18世纪末和19世纪,欧洲人和他们的北美后裔推翻了非洲、亚洲和南太平洋的本土文明,开始了政治文化的更替。 一个以大西洋为中心的新世界秩序已经形成。

这是一张白色地图,显示了掠夺最成功的欧洲帝国主义列强英国没有入侵的二十二个国家。

英国人从未入侵过的地图

欧洲国家通过本地区的竞争寻求安全和繁荣。 但为了在竞争中增强自己的实力,他们追求对海外资源和市场的控制,在海外建立军事基地,并将其公民安置在土著人口稀少但气候宜人的土地上。 结果是欧洲列强对全球的政治、技术和军事统治,以及欧洲人向美洲和澳大利亚温带地区的大规模移民。

第一次世界大战(1756 – 1815)

18世纪末19世纪初,英国和法国打响了第一次真正的全球战争。

https://i2.cdn.turner.com/cnnnext/dam/assets/150601134033-plumb-pudding-gillray-super-169.jpg

从 1756 年到 1815 年,他们的全球霸权之争时断时续,对其所定义的世界秩序中的国家和地区产生了决定性影响。 法国是一个绝对君主制国家,但它与英国的全球竞争使其有强烈的兴趣支持英国激进民主的美国殖民者反对他们的国王,尽管他们犯下了冒犯君主的罪行。 如果没有法国的干预,约克镇的美国独立决战就不会发生,殖民者的叛乱也可能不会成功。

全球欧洲 (1815 – 1914)

1815 年拿破仑最终失败后,维也纳会议通过将法国重新纳入其治理委员会来重建欧洲秩序。 所谓的欧洲协调建立了一个权力平衡体系,防止任何单一国家统治欧洲次大陆。 但随着 19 世纪的发展,英国在欧洲之外成为无可争议的全球霸主。

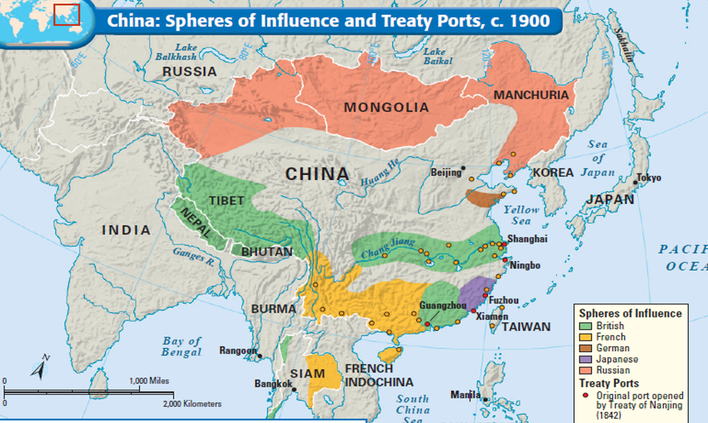

英国总督统治印度。 欧洲人瓜分了世界其他地区。 英、法、德、俄四国将中国划分为势力范围。

http://imperialisminchinaandjapan.weebly.com/uploads/9/8/6/2/98623894/published/spheres-of-influence-china.png?1487626178

比利时、英国、法国、德国、意大利、葡萄牙和西班牙瓜分了非洲,只留下埃塞俄比亚和利比里亚独立。

https://www.nicepng.com/png/detail/203-2034546_colonial-division-of-africa-scramble-for-africa.png

在西亚,只有沙特阿拉伯,在东亚,只有日本保持完全独立。 日本很快效仿欧洲帝国主义列强,建立了自己的海外帝国,于 1895 年占领了中国台湾省,于 1905 年征服了大韩帝国,并于 1910 年吞并了它。

相隔一个半球(1815 -?)

1815 年战胜对手法国后,英国进行了长达一个世纪的努力,试图阻止其欧洲对手获得美洲资源。 新生的美国与英国有着同样的利益,尽管它发现承认这一点是不明智的。

美国独立以及随后的 1789 年至 1799 年法国革命激励海地和西班牙在美洲的领地摆脱殖民统治并宣布独立。 到 1821 年,西班牙仅牢牢控制着古巴岛和波多黎各岛。

美国在 1823 年的“门罗主义”中宣布反对任何新的欧洲大国在拉丁美洲和加勒比地区的存在。 在实践中,鉴于华盛顿在“昭昭命运”学说下的弱点和专注于领土扩张,它依靠伦敦来执行其宣布的西半球战略封锁政策。 就这样,在英国的默许支持下,美国成功地将美洲从全球秩序中剔除,使它们免受欧洲帝国主义、殖民主义和文化霸权的影响,而这些在其他地方都取得了胜利。 美洲成为美国的势力范围。

美国加入俱乐部(1898 – 1934)

19世纪末,美国加入了帝国主义俱乐部,在夏威夷策划政权更迭并吞并它,然后从西班牙手中夺取了古巴、关岛、菲律宾和波多黎各。 英国认识到,在美洲,美国的实力已经超越了自己。 伦敦决定安抚并讨好华盛顿,而不是让英美之间的利益冲突和对抗引发一场可能让英国失去加拿大统治权的战争。 因此,它承认美国而不是加拿大对阿拉斯加狭长地带的主权,并撤回了对美国在巴拿马建设和管理跨地峡运河的反对意见。

1900 年,帝国主义时代达到顶峰,其中日本和美国作为最早的非欧洲实践者,八个殖民国家(奥匈帝国、英国、法国、德国、意大利、日本、俄罗斯和美国) )联合力量镇压反对外国控制中国的“义和团”叛乱并掠夺北京。

1903年,美国将巴拿马从哥伦比亚分离出去,开始了一个世纪的暴力干预,并在拉丁美洲和加勒比地区强行政权更迭。 在美国霸权下,西半球仍然是一个与整个世界秩序截然不同的地区。

美国作为跨大西洋平衡者、规则制定者和逃避者(1919 – 1929)

到1917年,英国已经改善了与美国的关系,以至于能够吸引美国人支持纠正因德国统一和崛起而导致的欧洲力量平衡崩溃的努力。 鉴于欧洲在全球事务中的主导地位,美国加入第一次世界大战对世界范围产生了影响。 美国前所未有地介入欧洲事务,成为世界最大经济体和债权国,标志着全球秩序的又一次变革。 但这一点需要一段时间才能变得明显。

在第一次世界大战中战胜德国后召开的 1919 年和平会议标志着国际社会承认美国作为大西洋和全球主要大国的地位。 在这次会议上,伍德罗·威尔逊总统主张美国对基于自决的世界秩序的愿景 — — 哪怕只是欧洲白人国家 — — 并用新的“联盟”下的法治取代国际强权政治。 国家的。” 他对自决的支持既反映了美国人对美国独立宣言的崇敬,也反映了他对家乡弗吉尼亚和童年居住地佐治亚所拥护的分离权的同情,这两个国家都是命运多舛的美利坚联盟国的不甘心的成员。 威尔逊关于基于商定的规范和监管机构的新世界秩序的理想主义愿景在会议上得到了口头支持,但除此之外几乎没有其他内容。 “自决”翻译成与欧洲和西亚相关的民族语言术语,为奥匈帝国和奥斯曼帝国的解体和分裂提供了理由。

长期以来,美国的核心意识形态就是法治。 “国际联盟”的提议代表了这种意识形态在国际事务中的投射。 随后美国拒绝加入国联,使其失去了能力,但受规则约束的秩序的理念继续在理想主义项目中得到体现,例如 1928 年的《凯洛格-布里安条约》,该公约的签署者道貌岸然地放弃使用战争来解决国际争端。 纠纷。

第一次世界大战使德国陷入瘫痪,使英国和法国陷入贫困,并促进了俄罗斯帝国的解体和苏联的重生。 包括美国在内的胜利者将德国和苏联排除在新的欧洲治理体系或权力平衡中发挥任何作用。 这种治国之术的失败导致了不稳定,并为二十年后欧洲重新爆发的霸权暴力斗争奠定了基础。

与此同时,1914 年至 1918 年的世界大战将美国推向全球经济、金融和文化的主导地位。 美元成为主要的国际交换媒介,美国音乐、文学和消费品赢得了全世界的赞誉。 但随着美国的自我孤立、欧洲列强的衰弱以及海外帝国独立呼声的高涨,世界陷入了日益混乱的状态 — — 正在向未知的方向转变。

大萧条和法西斯主义的兴起(1929 – 1939)

1929年,美国经济屈服于不受监管的资本市场的大规模投机、“美联储”的失误以及引发一系列贸易战的保护主义措施。这些事态发展的连锁反应所产生的全球苦难加速了更替。 德国和日本的民主与军国主义相结合,与意大利一起发展了“法西斯主义”的形式——由种族至上的社会达尔文主义理论、对领土扩张的痴迷和政府引导的法团主义经济驱动的独裁政权。

1931年,日本侵略中国,吞并了中国东北各省。 四年后,意大利入侵埃塞俄比亚。 1938年,德国并入捷克斯洛伐克。 1939年,意大利吞并阿尔巴尼亚和德国,苏联瓜分波兰。 1940年,德国征服了法国。 1941年,入侵苏联。

第二次世界大战及其创造的世界(1939 – 1945)

尽管遭受重创和四面楚歌的英国和遭受重创的中国拼命恳求,美国仍对欧洲和亚洲的战争置之不理。 但 1941 年 12 月,美国的制裁被日本视为生存威胁,引发日本对珍珠港以及菲律宾、印度支那、马来亚、新加坡、印度尼西亚和香港的绝望攻击。 在泰国盟友的帮助下,日本入侵缅甸。 四天后,德国、意大利及其辖区向美国宣战,美国也做出了回应。 这场竞赛现已成为全球性的。 第二次世界大战开始了。

到 1945 年结束时,第二次世界大战已经摧毁了之前的世界秩序,夺走了大约 70 至 8500 万人的生命,约占当时世界人口的 3%。 死亡人数中约有三分之一是苏联人,另外三分之一是中国人。 美国死亡人数接近 42 万人,英国死亡人数为 45 万人,法国死亡人数约为 60 万人。 德国失去了超过 700 万公民,日本失去了近 300 万公民。 战争结束时,只有美国的经济状况比以前好,其战时经济已增长至全球 GDP 的 60% 左右。

美国战时总统富兰克林·德拉诺·罗斯福了解建立新世界秩序的必要性,并设想建立一个建立在势力范围之上的世界秩序。 在他的理念中,英国首相温斯顿·丘吉尔认为英国将管理其全球帝国,中国将管理东亚,苏联将管理东欧和内亚,而美国将管理西半球。 虽然这一提议于 1945 年随着罗斯福的去世而夭折,但随着法国的加入,这一概念在联合国安理会拥有否决权的常任理事国的组成中继续存在。

世界秩序计划(1944 – 1945)

第二次世界大战期间,历史上第一次在全球范围内进行多国谈判,明确旨在制定新的世界秩序。 1944 年,44 个独立国家的代表齐聚新罕布什尔州北部的布雷顿森林度假村,就战后世界商业和金融关系以黄金和美元为基础的体系达成一致。 第二年,随着战争接近尾声,五十个国家的代表齐聚旧金山起草《联合国宪章》。 这奠定了国际法的基础,并为 1945 年 10 月(日本投降两个月后)正式成立联合国奠定了基础。 这一改进版国际联盟的总部设在纽约,反映了美国战后的优势地位以及对美国孤立主义可能卷土重来的担忧。

联合国关于以规则为指导的全球治理合作体系的愿景几乎立即成为大国对抗的牺牲品,但美国发起的规则建设却进展迅速。 《国际人权公约》和《灭绝种族罪公约》的历史可追溯至 1948 年。1949 年,规范战争行为的两项《日内瓦公约》得到更新,并获得了两项新公约。 随后制定了一系列禁止各种残忍行为的国际条约,包括禁止种族主义、歧视妇女和酷刑。 但到了 20 世纪 80 年代,这一势头有所减弱,这在很大程度上是由于美国对联合国和国际法的尊重减弱。

美国努力缔结1982年《联合国海洋法公约》,但随后拒绝批准。 同样的命运也降临到了国际社会自 1981 年以来通过的约二十个多边条约。在过去的四十年里,美国只是不稳定地参与了它在第一次世界大战后努力建立的基于法律的世界秩序 和第二次世界大战时期。

冷战秩序(1947 – 1989)

到 1947 年,以苏联和美国霸主为首的敌对集团开始在地缘政治和意识形态问题上相互对抗。 这两个争论的根源在 1947 年杜鲁门主义支持希腊和土耳其对抗苏联压力、1948 年至 1949 年柏林危机以及 1950 年至 1953 年血腥的朝鲜战争中都很明显。这些事件建立了一个准封建的两极世界秩序 这种情况一直持续到1989年,苏联的东欧帝国解体,它不再争夺欧亚或全球霸权。

在冷战的四十年里,民族国家与一个或另一个超级大国的关系(或缺乏关系)决定了它们的地缘政治地位、行动自由、获得公共物品的水平以及免受外国煽动的豁免程度。 政权更迭行动。 与此同时,相互竞争的超级大国开始期望那些与他们结盟的国家自动追随他们在世界事务各个方面的立场。

美国和苏联都小心翼翼地防止各自势力范围内的国家溜走或投奔对方,但两国都意识到核交锋中相互毁灭的危险,而且双方都不准备冒这种风险进行交战。 与对方直接战斗。 两国都认为试图保持不结盟 — — 与任何一个集团分离 — — 的新独立国家都是意志薄弱且容易被争夺的,并且各自都试图通过代理人战争、政权更迭行动、操纵选举和政治活动来维持或扩大其势力范围。 经济上的奉承和剥夺。

与之前的世界秩序相比,意识形态是冷战时期更加突出的特征。 以美国为首的集团 — — 所谓的“自由世界” — — 政治上是异质的。 它由民主政体、独裁政体、君主政体和帝国前哨的混合体组成,除了希望不被无神论的共产主义所征服并通过与美国结盟来获取物质利益之外,没有什么共同点。 其成员国实行多种形式的资本主义、社会民主主义和宗教信仰。

相比之下,苏联集团的成员相对单一。 他们的政治以马克思列宁主义、残酷的精英独裁、无神论意识形态和莫斯科倡导的国家主义政治经济体系为蓝本。

冷战时期的外交与堑壕战非常相似。 其目的不是缩小对方的势力范围,而是避免给对方攻击自己的理由。 尽管双方都在努力颠覆对方,但这两个集团在长达四个十年的对抗过程中仍然非常稳定。 两个超级大国都在各自称为“盟友”的集团成员的领土上驻军,这意味着他们承诺确保其免受对方攻击或意识形态转变的附属国家。 双方都限制这些“盟友”针对对方采取可能升级为双边战争的行动。 冷战秩序的结束消除了苏联对伊拉克等国家的限制,伊拉克随后可以随意在阿拉伯半岛发动一场扩张战争,而在苏联的监督下,这些国家永远不敢冒险。

对冷战秩序单调稳定的最大冲击是 1971 年至 1979 年美国加入中国遏制苏联。 中国向所谓“自由世界”的转变实现了再平衡,但并没有改变当时世界秩序的基本性质。 这仍然是由美国及其集团与苏联及其辖区之间的对抗性互动所决定的。 除了美国与中国的协约以及南斯拉夫早些时候转向中立之外,几乎没有人背叛这两个集团。 只有一件事——古巴转向苏联的保护——促成了两个超级大国之间核对峙的濒临死亡的经历。 巧妙的外交避免了灾难。

殖民主义的终结(1947 – 1997)

第二次世界大战结束后,欧洲帝国曾试图收复二战期间失去的海外领土,但未能成功。 几个世纪以来欧洲的全球统治地位将基督教西方文化的元素强加于其海外领地,包括大西洋地区的主要语言和公开的价值观。

其中包括植根于民众选举的代议制政府规范,这与帝国统治固有的暴政存在明显的冲突。 具有讽刺意味的是,欧美殖民列强的意识形态和政治文化最终激发了全球南方国家争取独立的斗争。

输出的西方意识形态包括马克思主义,它最初是一种基于哲学和社会科学的批评,批评西方文明未能培养其宗教信仰和理想所需的个人和集体的自我实现、平等主义和博爱。 在中国和其他地方,马克思主义是一种受欢迎的西化手段,同时也贬低了西方。 与列宁主义 — — 一套组织精英一党专政以重新设计社会经济体系并指导其发展的政治原则 — — 相结合,它被证明是革命和政治经济转型的有力工具。

欧洲帝国主义的撤退为两个公开反对殖民主义的“超级大国”之间的斗争创造了新的舞台。 从1941年到1945年,日本强行用自己的统治取代了欧洲在东亚和东南亚的统治。 它的失败留下了一个权力真空,被胜利的美国占据。 在缅甸和印度,日本对亚洲的主张引起了缅甸和印度民族主义者的共鸣,他们于 1947 年从英国手中夺取了独立。1945 年至 1949 年间,美国控制的菲律宾、荷兰印度尼西亚、英属印度、巴基斯坦、缅甸 、锡兰都在殖民统治者的暴力反对下获得了独立。 这些国家争取自决的斗争造成了数百万人的伤亡。

1949年,作为加入北约的条件,法国要求归还其在印度支那的殖民地。 但到了 1954 年,越南共产党军队迫使他们接受越南北部以及柬埔寨和老挝的独立。 此后,在1954年至1975年的“第二次印度支那战争”中,北越击败了南越及其赞助者美国。 在越南争取民族自决的斗争中,三百万或更多的越南平民和战斗人员死亡。 北方战胜南方后,200万越南人在国外寻求庇护,另外100万人死于海上。 20 世纪 60 年代初,法国赋予其非洲殖民地政治独立,但在经济上仍对它们保持忠诚。

相比之下,1957 年,英国效仿了印度和缅甸的先例,开始了给予其最坚持的殖民地完全独立的进程,首先是马来亚和加纳。 1952年至1963年的毛毛起义中,英国殖民者殖民主义在肯尼亚遭受了致命打击。1980年,经过长达十年的血腥战争,津巴布韦摆脱了南罗得西亚的白人统治。 到 1990 年,最后一个非洲殖民地——纳米比亚——获得了独立。 1997年,英国最后一个非自治殖民地香港回归中国。 长达五个世纪的帝国主义时代结束了。 现在唯一剩下的侵略性定居者殖民主义的践行者是以色列,只有美国在联合国安理会的否决权才使其免受国际谴责和制裁。

冷战的后果(1989 – 2007)

美国外交官乔治·凯南 (George Kennan) 在 1946 年提出了“遏制”苏联的大战略,他的判断是,如果孤立,苏联最终会因自身缺陷而崩溃。 我们花了四十多年的时间才证明他是对的。 1991年苏联解体以及其组成的波罗的海、东欧和中亚共和国独立后的几年里,正如弗朗西斯·福山所宣称的那样,历史似乎以自由民主的胜利而结束。 但事实并非如此。 西方的骗子对苏联经济进行了彻底的重组,使人民陷入贫困,但却让新的富豪和寡头阶层变得富有。 俄罗斯与西方融合的努力遭到了矛盾、不受欢迎和令人反感的回应。

在冷战刚结束的时期,没有人质疑美国的全球霸主地位。 实际上,华盛顿掌控着一个仅排除中国、伊朗、朝鲜和俄罗斯的全球势力范围,它可以在其中为所欲为,而无需考虑《联合国宪章》、国际法或其他国际互动准则。 早些时候曾帮助开过处方。 与此同时,贸易和投资自由化、全球化给包括中国和南方国家在内的世界经济带来了新的财富。

但资源密集型“永久战争”和反恐运动所带来的必胜主义和注意力缺失外交使美国失去了与新崛起的俄罗斯联邦建立合作关系的任何战略。 相反,西方将俄罗斯视为潜在敌人的传统观点盛行。 在莫斯科仇俄邻国及其美国侨民、因敌人剥夺综合症而迷失方向的军工国会复合体、冷战顽固老兵以及习惯势力的压力下,对俄罗斯的恐惧仍然是北约的指导精神。

俄罗斯的反应(1994 – 2008)

早在1994年,俄罗斯就开始警告美国,如果北约东扩扩大到俄罗斯边境,莫斯科将视其为敌对证据并采取军事回应。 但到了 2004 年,前苏联主导的华沙条约组织的所有成员国都已加入北约。 冷战期间,北约是一个纯粹的防御性联盟,旨在对抗欧洲的莫斯科。 但1995年,北约开始采取攻势。 它对波斯尼亚和黑塞哥维那进行了干预。 1999年,它发动了为期78天的轰炸行动,从传统上与俄罗斯有联系的塞尔维亚手中夺取了科索沃。 2001年,北约与美国一起参与了长达20年的战争,以平息遥远的阿富汗。 2011年,它支持了一场政权更迭行动,导致利比亚陷入无政府状态。 随着北约向俄罗斯扩张,莫斯科开始将其视为日益活跃的军事威胁。

2007年,俄罗斯总统普京对北约进一步东扩发出强烈警告。 但2008年,在美国的压力下,北约向格鲁吉亚和乌克兰提供了成员国资格,这两个国家都是与俄罗斯联邦接壤的前苏联成员国。 随后,勇敢的格鲁吉亚挑战了俄罗斯在其与俄罗斯边境的少数民族地区的影响力。 结果是21世纪的第一次欧洲战争,最终以俄罗斯协助下南奥塞梯和阿布哈兹从格鲁吉亚分裂出去并在那里建立宗主权而告终。

顿巴斯代理人战争(2014 年 -?)

2014年,一场美国支持的政变推翻了民选但腐败的亲俄政府。 政变后,美国再次向北约施压,要求将乌克兰纳入其中。 乌克兰加入北约可能带来的后果之一是剥夺俄罗斯在克里米亚拥有数百年历史的黑海海军基地。 随后,俄罗斯不流血地使用了非战争军事措施,收回了克里米亚,苏联于 1954 年将克里米亚的行政控制权从俄罗斯移交给了乌克兰。

与此同时,基辅新的极端民族主义政权试图使乌克兰语成为全国公共机构官方和人际交流的唯一语言,结束在国家和地区层面官方使用俄语和其他少数民族语言。 此后不久,俄罗斯在克里米亚举行了全民公投,克里米亚的大多数居民——其中四分之三以上的母语是俄语——欢迎克里米亚重新并入俄罗斯联邦。 顿涅茨克和卢甘斯克的顿巴斯州,讲俄语的人口占人口的百分之七十或以上,随后宣布脱离乌克兰自治,这一决定得到了俄罗斯的支持。

乌克兰发动攻势,收复了顿巴斯部分地区。 俄罗斯向分裂分子提供军事援助作为反击。 在联邦化的乌克兰内恢复语言和其他自治要素的外交努力产生了两项从未实施的协议(在明斯克)。 随着顿巴斯战争在偶尔停火的情况下进行,乌克兰在顿巴斯建立了一系列防御工事,每天都从那里轰炸分裂分子,而俄罗斯帮助他们建立了强大的军队。 美国、英国和其他北约成员国为重新训练、重组和重新装备乌克兰军队做出了重大努力。 俄罗斯同时加大了对顿巴斯分裂分子的军事支持。

北约东扩战争、中美关系疏远、中俄协约

2021年底,俄罗斯要求进行谈判以排除乌克兰加入北约的可能性。 美国和北约拒绝讨论此事。 俄罗斯在与乌克兰边境集结军队。 美国和北约再次拒绝莫斯科就北约东扩问题进行谈判的要求。 2022年初,俄罗斯承认顿涅茨克和卢甘斯克独立,驻军并入侵乌克兰。

作为回应,美国与欧盟、英国、澳大利亚和其他一些安全伙伴一起,对俄罗斯发动了全面经济战,将其从以美元为基础的全球贸易体系中剔除,试图禁止其能源出口 ,并夺取其美元储备,同时向乌克兰发起大规模武器转让和战术情报支持,乌克兰目前正陷入与俄罗斯长达数千公里的消耗战。

西方对俄罗斯入侵乌克兰的反应伴随着信息战,这是世界历史上最激烈、最全面的信息战。 由于除了有利于乌克兰的信息来源之外的所有信息来源都被切断,因此不可能了解那里到底发生了什么。 西方支持乌克兰代理人战争的政策是否能够挽救乌克兰并恢复欧洲和平充其量是值得怀疑的,但对俄罗斯的经济战争及其连锁反应,随之而来的中美关系的爆发以及世界范围的转变 国家安全而不是经济问题驱动的保护主义共同催化了一种全新的国际互动模式的出现。

另一个尚未命名的世界秩序的无序诞生(2022 -?)

美国在乌克兰发动战争的直接目标是维护基辅与美国和欧盟保持结盟的自由,即使不是现在加入北约。 美国的长期战略目标明确是“孤立和削弱俄罗斯”。

美国对华政策与这些目标相一致。 华盛顿寻求将台湾留在其势力范围内,并孤立和削弱中国,以保持其地区和全球经济、技术以及政治军事霸权。 毫不奇怪,北京和莫斯科已经认识到,阻挠和对抗美国旨在从属于它们、阻碍它们财富和权力增长的政策是共同利益。

美国与俄罗斯和中国的对抗政策没有得到大多数北约国家和日本的热情支持。 但巴西、印度、印度尼西亚、伊朗、墨西哥、尼日利亚、巴基斯坦、沙特阿拉伯、南非和土耳其等崛起和复兴大国反对美国延续它们所代表的“单边时刻”的努力。 除了澳大利亚、英国、日本和韩国等明显例外,其他主要国家显然更喜欢多极、多中心的世界秩序,而不是由美国或任何其他单一大国主导的世界秩序。

到目前为止,特朗普政府2018年针对中国推出的保护主义贸易和技术政策以及当前针对俄罗斯的经济和金融战争正在产生有害的结果。 中国科学技术和军事进步加快。 俄罗斯经济远未崩溃,目前拥有仅次于中国的第二大国际收支顺差。 与此同时,欧洲人面临经济衰退、能源短缺和其他困难。 中国和俄罗斯都在为其商品和服务寻找新市场。 乌克兰战事尚无结束迹象,台海爆发战争的可能性急剧上升。

未来事物的形态

正在出现的世界秩序是:

制裁引发的商品和食品短缺、供应链断裂以及重新军备加剧了持续的通货膨胀。

利息支付增加的财政负担迫使美国转向国内现收现付政策,并在美国长期以来回避的“大炮和黄油”之间做出选择。

由美国、欧盟、澳大利亚、英国和日本组成的旨在排斥俄罗斯和中国的集团本身就被世界其他国家边缘化,包括其增长最快的经济体和市场。 以美国为首的集团以外的国家拒绝在美国及其指定对手之间做出选择,保持与这两个国家的业务开放,并拒绝西方对其出口产品施加最终用途和再转让限制。

全球范围内应对气候变化和流行病等问题的能力受到削弱。 每个地区都是独立的,就其影响而言,部分之和小于整体。

事实证明,美国的主要优势——军事实力——与新兴世界秩序中的大多数挑战无关,这些挑战需要华盛顿无法采取的经济应对措施。

俄罗斯永久放弃了长达三个世纪的与欧洲一体化的努力,以通过加强与中国和印度的关系来寻求亚洲身份。

土耳其也做了同样的事情,将自己重新定义为西亚和伊斯兰国家,而不是欧洲国家,并进一步削弱了对北约其他成员国的承诺。

小国拒绝与西方或其指定对手有任何联系。

中国的“一带一路”倡议逐渐将中国的经济影响力扩展到整个欧亚大陆以及东南亚和东非。 中国在“一带一路”沿线地区的政治影响力逐渐取代美国。

北约和其他多国联盟的凝聚力逐渐减弱,成员国逐渐减少或撤销对它们的承诺。

德国、日本和其他二战后美国的附属国重新武装并制定更加独立的外交政策。

拉丁美洲与中国、印度、伊朗、俄罗斯、土耳其和其他国家发展关系,这些国家日益削弱美国在西半球的霸权。

非洲是世界上大多数工业劳动力居住的地方,其经济与巴西、中国、印度、俄罗斯和土耳其的联系比与欧盟或美国的联系更加紧密。

技术标准因地区而异,新技术往往在其起源地以外的地区无法获得。

互联网演变成区域和国家区域,通过防火墙相互隔离。

廉价的俄罗斯能源、金属、矿产和其他自然资源滋养了所谓的“全球南方”的经济,但美国及其反俄联盟成员不再能以优惠的价格可靠地获得这些资源。

美国的制裁使中国和俄罗斯有强烈的动机与伊朗和其他国家组成财团,以消除在民用、军用和客机等军民两用产品方面对美国的依赖。

鉴于美国没收伊朗、委内瑞拉、俄罗斯和阿富汗的美元储备所造成的声誉损害,美国通过发行国债为其政府和全球实力投射提供资金的能力越来越受到质疑。

美国单边美元制裁带来的风险不断上升,导致越来越多的国家以本国货币为进出口定价,利用掉期将本国货币与主要贸易伙伴的货币配对,转向美元以外的硬通货,并建立了以下观点: 销售数字跨境货币兑换,并为跨国贸易结算创建新的记账单位。 支撑美国全球霸主地位的“过高特权”正在消失。

中国、印度、俄罗斯、阿拉伯石油生产国和其他新兴经济和金融大国对建立独立的金融世界秩序的动机做出了反应,该秩序为基于美元的 SWIFT 系统提供了替代方案,并可能破坏美国制裁作为制裁工具的有效性。 对外政策。 他们这样做了。

去全球化产生了多种区域贸易和投资体制,并分裂了全球市场,其中一些特定大国,如中国、欧盟、印度、俄罗斯或美国被排除在外。

国际交易的争端是通过双边或特定地区的程序来处理的,而不是通过像世贸组织这样的全球争端解决机制来处理。

世界继续依赖联合国专门机构来解决技术问题,但联合国安理会和其他国际政策组织因大国竞争和分歧而陷入瘫痪,外交效用已经减弱。

与区域性不同,新的全球规则制定条约和安排很少(如果有的话)。 冷战后时代的全球监管制度萎缩。

随着地区力量的增强以及中国、印度、日本、韩国和俄罗斯出现新的武器系统和能力,美国的军事霸主地位受到削弱。

鉴于美国、北约和俄罗斯在乌克兰的代理人战争升级的风险、中美就台湾问题爆发战争的可能性日益增加、朝鲜政权生存依赖核威慑、印度和巴基斯坦的核对峙以及 如果以色列核武库向其地区其他国家获取核武器,核战争的危险现在比冷战时期的任何时候都要大得多。

结论

国际社会对20世纪末日益衰落的“美国治下的和平”非常不满,并希望看到它被多极世界秩序或不同国家在世界事务不同领域发挥主导作用的秩序所取代。 当前的趋势表明,万花筒再次以新的模式重新安排国际参与者及其关系,在这种模式中,经济、金融、政治、文化和军事实力按区域和职能分布,而不是集中。 但迄今为止,很少有人考虑到国际体系可能产生的后果,因为该体系需要国家和人民之间的互动比以前更加复杂。 如果不出意外的话,这正好提醒我们一句老话:“小心你的愿望”。 你可能会得到它。

为了成功应对这个拥有众多竞争中心的世界所带来的挑战,治国之道必须着眼长远,关注持久的利益而不是一时的激情。 为了管理一个快速、意想不到的变化成为常态的世界,外交必须灵活而不是坚定。 为了能够竞争,各国不仅必须在国内齐心协力,还必须运用所有治国手段——政治、经济、金融、技术和军事——来塑造竞争对手的观点和行动,使其对自己有利。

mmm

World Orders: The Global Kaleidoscope in Repeated Motion

https://chasfreeman.net/world-orders-the-global-kaleidoscope-in-repeated-motion/

Chas Freeman 2022-09

Ambassador Chas W. Freeman, Jr. (USFS, Ret.)

Visiting Scholar, Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs, Brown University

By video from Washington, DC 21 September 2022

The world is now in a confusing transition to a new order for both its constituent regions and its functional divisions. This is not unusual. In the five centuries since all parts of the globe were brought into mutual communication, there have been many such evolutions.

The first global, as opposed to regional order emerged only in the final years of the 15th century. In 1492, Columbus crossed the Atlantic. This connected the Americas to Europe. Soon after, in 1498, Vasco da Gama circumnavigated Africa and reached India. These two events for the first time made all the world’s continents and oceans a single geopolitical and geoeconomic playing field. They also inaugurated a four-century-long period in which rapidly advancing European technology, industry, and military capabilities bested all competitors, and Western imperialism, colonialism, and ideas conquered the globe.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, Europeans exterminated most of the indigenous inhabitants of the Americas, became the predominant populations there, and began the transport of millions of enslaved Africans across the Atlantic. In the late 18th and the 19th centuries Europeans and their North American descendants overthrew the indigenous civilizations of Africa, Asia, and the South Pacific and began the replacement of their political cultures. A new, Atlantic-centered world order had come into being.

Here is a map showing in white the twenty-two countries that the most successfully predatory European imperialist power, Britain did not invade.

European states sought security and prosperity through competition in their own region. But to strengthen themselves in that competition, they pursued control of overseas resources and markets, established military bases abroad, and settled their citizens in lands with sparse indigenous populations but congenial climates. The result was the political, technological, and military domination of the globe by Europe’s great powers, and mass migration by Europeans to the temperate zones of the Americas and Antipodes.

The first worldwide war (1756 – 1815)

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the British and French fought the first truly global war.

Their battle for global hegemony flared on and off from 1756 to 1815. with decisive effects on the countries and regions within the world order it defined. France was an absolute monarchy but its worldwide contest with Britain gave it a compelling interest in supporting Britain’s radically democratic American colonists against their king despite their crime of lèse majesté. Absent French intervention, the decisive battle for American independence at Yorktown would not have occurred and the colonists’ rebellion might not have succeeded.

Global Europe (1815 – 1914)

After the final defeat of Napoleon in 1815, the Congress of Vienna reconstituted order in Europe by reintegrating France into its councils of governance. The so-called Concert of Europe established a balance of power system that prevented any single power from dominating the European subcontinent. But as the 19th century proceeded, outside Europe Britain emerged as the undisputed global hegemon.

A British viceroy ruled India. Europeans divided the rest of the world between them. Britain, France, Germany, and Russia sliced China into spheres of influence.

Belgium, Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Portugal, and Spain apportioned Africa between them, leaving only Ethiopia and Liberia independent.

In West Asia, only Saudi Arabia, and in East Asia, only Japan remained completely independent. Japan soon emulated Europe’s imperialist powers by building its own overseas empire, seizing the Chinese province of Taiwan in 1895, subjugating the Empire of Korea in 1905, and annexing it in 1910.

A hemisphere apart (1815 -?)

After its 1815 victory over its French adversary, Britain made a century-long effort to deny the resources of the Americas to its European rivals. The newborn United States shared this British interest, even if it found it impolitic to acknowledge this. U.S. independence, followed by the French revolution of 1789 – 1799, had inspired Haiti and the Spanish fiefdoms in the Americas to throw off colonial rule and declare their own independence. By 1821, Spain was in firm control only of the islands of Cuba and Puerto Rico.

In its 1823 “Monroe Doctrine,” the United States declared its opposition to any new European great power presence in Latin America and the Caribbean. In practice, given its weakness and concentration on territorial expansion under the doctrine of “Manifest Destiny,” Washington relied on London to enforce its declared policy of hemispheric strategic denial. In this way, with tacit British backing, the United States managed to subtract the Americas from the global order, exempting them from the European imperialism, colonialism, and cultural supremacy that were everywhere else triumphant. The Americas became a U.S. sphere of influence.

America joins the club (1898 – 1934)

As the 19th century ended, the United States itself joined the imperialist club, engineering regime change in Hawaii and annexing it, then seizing Cuba, Guam, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico from Spain. Britain recognized that, in the Americas, U.S. power had eclipsed its own. Rather than allow Anglo-American conflicts of interest and confrontations to spark a war that might cost Britain its Canadian dominion, London decided to appease and court Washington. So, it recognized U.S. rather than Canadian sovereignty in the Alaska Panhandle and withdrew its objections to the U.S. construction and management of a trans-Isthmian canal in Panama.

In 1900, in a culmination of the age of imperialism that included Japan and the United States as its first non-European practitioners, eight colonial powers (Austria-Hungary, Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Russia, and the United States) combined forces to suppress the “Boxer” rebellion against foreign control in China and to pillage Beijing.

In 1903, the United States detached Panama from Colombia and began a century of violent interventions and imposed regime changes in Latin America and the Caribbean. Under American hegemony, the Western Hemisphere remained a region distinct from the world order at large.

America as transatlantic balancer, rule giver, and cop-out (1919 – 1929)

By 1917, Britain had improved its relations with the United States to the point that it was able to draw Americans into support of efforts to redress the breakdown of the balance of power in Europe brought about by the unification and rise of Germany. Given Europe’s dominance of global affairs, the U.S. entry into World War I had worldwide effects. The unprecedented involvement of the United States in European affairs and America’s status as the world’s largest economy and creditor nation marked yet another transformation of the global order. But it took time for this to become apparent.

The 1919 peace conference that followed victory over Germany in the First World War marked international recognition of the United States as a leading Atlantic and global power. At the conference, President Woodrow Wilson advocated a distinctly American vision of world order based on self-determination – if only for the white nations of Europe – and the replacement of international power politics with a version of the rule of law under a new “League of Nations.” His support for self-determination reflected both popular American reverence for the U.S. declaration of independence and his own sympathy for the right of secession espoused by his native Virginia and childhood residence in Georgia, both unreconciled members of the ill-fated Confederate States of America. Wilson’s idealistic vision of a new world order based on agreed norms and regulatory institutions gained lip service at the conference, but little else. Translated into ethno-linguistic terms relevant to Europe and West Asia, “self-determination” furnished the justification for the dismantling and partition of the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires.

America’s core ideology had long been the rule of law. The proposal for a “League of Nations” represented a projection of this ideology into international affairs. The subsequent refusal of the United States to join the League incapacitated it, but the idea of a rule-bound order continued to find expression in idealistic projects like the Kellogg-Briand Pact of 1928, whose signatories sanctimoniously renounced the use of war to settle international disputes.

The First World War had crippled Germany, gutted and impoverished Britain and France, and catalyzed the dissolution and rebirth of the Russian Empire as the Soviet Union. The victors, including the United States, excluded both Germany and the Soviet Union from any role in a renewed European system of governance or balance of power. This miscarriage of statecraft ensured instability and laid the basis for a renewed violent struggle for hegemony in Europe two decades later.

Meanwhile, the world war of 1914 – 1918 had propelled the United States to global economic, financial, and cultural preeminence. The dollar became a major international medium of exchange, and American music, literature, and consumer products achieved worldwide acclaim. But with the United States self-isolated, the great powers of Europe weakened, and agitation for independence in their overseas empires mounting, the world was in a state of increasing disorder – in transition to something yet unknown.

The great depression and the rise of fascism (1929 – 1939)

In 1929, the American economy succumbed to mass speculation in its unregulated capital markets, blunders by the “Fed,” and protectionist measures that kicked off a series of trade wars The global misery generated by the knock-on effects of these developments precipitated the replacement of democracy with militarism in Germany and Japan, which joined Italy in developing forms of “fascism” – dictatorial regimes driven by social Darwinist theories of racial supremacy, obsessions with territorial expansion, and government-guided corporatist economies.

In 1931, Japan invaded China and annexed its northeastern provinces. Four years later, Italy invaded Ethiopia. In 1938, Germany took part of Czechoslovakia. In 1939, Italy annexed Albania and Germany and the Soviet Union partitioned Poland. In 1940, Germany conquered France. In 1941, it invaded the Soviet Union.

World War II and the world it created (1939 – 1945)

Despite desperate pleas from a battered and beleaguered Britain and a decimated China, the United States stood aside from the wars in Europe and Asia for two years. But in December 1941, U.S. sanctions regarded by Japan as an existential threat provoked it into a desperate attack on Pearl Harbor as well as the Philippines, Indochina, Malaya, Singapore, Indonesia, and Hong Kong. With help from its Thai allies, Japan invaded Burma. Four days later, German, Italy, and their satrapies declared war on the United States, which reciprocated. The contest was now global. A second world war had begun.

By the time it ended in 1945, World War II had smashed the previous world order and taken the lives of an estimated 70 – 85 million people or about 3 percent of the world’s then population. About one-third of the deaths were Soviet, another third Chinese. American deaths came to almost 420,00, British to 450,000, and French to about 600.000. Germany lost over seven million citizens and Japan almost three million. At the war’s end, only the United States, whose wartime economy had grown to about 60 percent of global GDP, was better off than it had been.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the U.S. wartime president, understood the need for a new world order and imagined one built on spheres of influence. In his concept, which Britain’s Prime Minister Winston Churchill found congenial if charmingly naïve, Britain would manage its global empire, China would manage East Asia, the Soviet Union would manage eastern Europe and inner Asia, and the United States would manage the Western Hemisphere. While this proposal died with Roosevelt in 1945, the concept lived on – with the addition of France – in the composition of the United Nations Security Council’s veto-wielding permanent members.

A plan for world order (1944 – 1945)

During World War II, for the first time in history, multinational negotiations took place on a global basis explicitly to craft a new world order. In 1944, the representatives of forty-four independent nations gathered at the Bretton Woods resort in northern New Hampshire to agree on a gold and dollar-based system for the postwar world’s commercial and financial relations. The following year, as the war neared its end, the representatives of fifty nations convened in San Francisco to draft the Charter of the United Nations. This set out the fundamentals of international law and provided the basis for the formal establishment of the UN in October 1945, two months after the Japanese surrender. Reflecting the post-war ascendancy of the United States and concerns about a possible renewal of American isolationism, the headquarters of this improved version of the League of Nations was in New York.

The UN vision of a cooperative system of rule-guided global governance almost immediately fell victim to great power antagonism, but US-sponsored rule-building proceeded apace. The International Convention on Human Rights and the Genocide Convention date to 1948. In 1949, the two Geneva Conventions regulating the conduct of war received an update and gained two new conventions. A wide range of international treaties prohibiting various cruelties followed, including bans on racism, discrimination against women, and torture. But by the 1980s, the momentum slackened, in large measure due to flagging U.S. deference to the UN and international law. The United States worked hard to conclude the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea but then declined to ratify it. The same fate befell some twenty other multilateral treaties adopted by the international community since 1981. For the past four decades, the U.S. has participated only erratically in the law-based world order it had worked so hard to establish in the post-World War I and World War II periods.

The Cold War order (1947 – 1989)

By 1947, rival blocs led by Soviet and American overlords had begun to confront each other over both geopolitical and ideological issues. Both sources of contention were evident in the 1947 Truman Doctrine’s support for Greece and Turkey against Soviet pressure, the 1948 -1949 Berlin crisis, and the appallingly bloody Korean War of 1950 – 1953. These events put in place a quasi-feudal bipolar world order that lasted until 1989, when the Soviet Union’s eastern European empire disintegrated, and it ceased to contend for Eurasian or global hegemony.

During the four decades of the Cold War, the relationship – or lack of relationship – of nation states with one or the other superpower determined their geopolitical positions, freedom of maneuver, level of access to public goods, and degree of immunity from foreign-instigated regime change operations. Meanwhile, the contending superpowers came to expect automatic followership from those aligned with them for their positions on each and every aspect of world affairs.

The U.S. and the Soviet Union took care to prevent states in their respective spheres of influence from slipping away or defecting to the other, but both were conscious of the danger of mutual annihilation in a nuclear exchange, and neither was prepared to risk this by engaging in direct combat with the other. Both saw newly independent states that attempted to remain nonaligned – separate from either bloc – as weak-minded and up for grabs, and each sought to sustain or expand its sphere of influence through proxy wars, regime change operations, the manipulation of elections, and economic blandishments and deprivations.

Ideology was a much more prominent feature of the Cold War than it had been in previous world orders. The US-led bloc – the so-called “free world” – was politically heterogeneous. It was composed of a mixture of democracies, dictatorships, monarchies, and imperial outposts with little in common other than a desire to remain unsubjugated by godless communism and to derive material benefits through alignment with the United States. Its member states practiced multiple versions of capitalism, social democracy, and religious faith.

The members of the Soviet bloc, by contrast, were relatively homogeneous. They modeled their politics on Marxism-Leninism, the ruthless elitist dictatorship, atheist ideology, and statist political economic system championed by Moscow.

Diplomacy in the Cold War resembled nothing so much as trench warfare. Its object was less to roll back the spheres of influence of the other side than to avoid giving the other a reason to attack it. Despite the efforts of each side to subvert the other, the two blocs remained remarkably stable over the course of their four-decade-long confrontation. Both superpowers kept garrisons on the territories of those members of their blocs they termed “allies,” by which each meant subordinate states they had committed to secure against attack or ideological conversion by the other. Each restrained such “allies” from actions against the other that might escalate into bilateral warfare between them. The end of the Cold War order removed Soviet constraints on countries like Iraq, which then felt free to launch a war of expansion in Arabia it would never have dared to risk when subject to Soviet supervision.

The greatest shock to the boring stability of the Cold War order was the 1971 – 1979 U.S. enlistment of China in the containment of the Soviet Union. China’s shift to the so-called “free world” rebalanced but did not alter the fundamental nature of the world order of the time. This remained defined by adversarial interactions of the United States and its bloc and the Soviet Union and its satrapies. Aside from the U.S. entente with China and an earlier shift to neutrality by Yugoslavia, there were few defections from either bloc. Only one — Cuba’s turn to Soviet protection – catalyzed the near-death experience of a nuclear standoff between the two superpowers. Deft diplomacy kept disaster at bay.

The end of colonialism (1947 – 1997)

In the immediate aftermath of World War II, Europe’s empires had tried and failed to recover the overseas dominions they had lost during World War II. Centuries of European global dominance had imposed elements of the Christian West’s culture on its overseas possessions, including the Atlantic region’s major languages and professed values. These included norms of representative government rooted in popular elections, with which the tyranny inherent in imperial rule was in obvious conflict. Ironically, the ideologies and political cultures of the Euro-American colonial powers ended up inspiring the global South’s struggles for independence from them.

The exported Western ideologies included Marxism, which had begun as a philosophical and social science-based critique of Western civilization’s failure to foster the individual and collective self-fulfillment, egalitarianism, and fraternity that its religious faith and ideals required. In China and elsewhere, Marxism served as a welcome means by which to westernize while simultaneously disparaging the West. Allied with Leninism – a set of political principles for organizing an elite one-party dictatorship to reengineer socioeconomic systems and direct their development – it proved a potent tool of revolution and politico-economic transformation.

The retreat of European imperialism created new arenas for the struggle between the two “superpowers,” both of which were avowedly anti-colonialist. From 1941 to 1945 Japan had forcibly replaced European rule in East and Southeast Asia with its own. Its defeat left a power vacuum that was occupied by the victorious United States. In Burma and India, Japan’s advocacy of Asia for the Asians had resonated with Burmese and Indian nationalists, who wrested their independence from Britain in 1947. Between 1945 and 1949, the US-held Philippines, Dutch Indonesia, and British India, Pakistan, Burma, and Ceylon all achieved independence over often violent opposition by their colonial masters. The casualties involved in the struggles of these countries for self-determination numbered in the millions.

In 1949, as a condition for joining NATO, the French demanded the return of their colonies in Indochina. But, by 1954, Vietnamese communist forces had forced them to accept the independence of northern Vietnam as well as Cambodia and Laos. Thereafter, in the “Second Indochina War” of 1954 – 1975, north Vietnam defeated both south Vietnam and its American sponsor. In the Vietnamese struggle for national self-determination, three million or more Vietnamese civilians and combatants died. After the north’s victory over the south, as two million Vietnamese sought asylum abroad, another million perished at sea. France gave political independence to its African colonies in the early 1960s but locked them into continued economic fealty.

In 1957, by contrast, Britain followed the precedent it had set in India and Burma and began the process of conferring full independence on its most insistent colonies, beginning with Malaya and Ghana. British settler colonialism suffered a mortal blow in Kenya in the Mau Mau uprising of 1952 – 1963. In 1980, after a bloody ten-year-long war, Zimbabwe emerged from white rule in Southern Rhodesia. By 1990, the last African colonial territory – Namibia – had achieved independence. In 1997, the last non-self-governing British colony, Hong Kong, reverted to China. The five-century-long age of imperialism had ended. The sole remaining practitioner of aggressive settler colonialism is now Israel, which only the U.S. veto in the UN Security Council has shielded from international censure and sanctions.

The aftermath of the Cold War (1989 – 2007)

The American diplomat George Kennan based his 1946 proposal for a grand strategy of “containment” of the Soviet Union on his judgment that, if isolated, it would eventually collapse of its own defects. It took more than four decades to prove him right. For a few delirious years immediately after the 1991 implosion of the USSR and the independence of its constituent Baltic, eastern European, and central Asian republics, it seemed that, as Francis Fukuyama declared, history had ended in the triumph of liberal democracy. But this was not to be. Western carpetbaggers administered a drastic restructuring of the Soviet economy that immiserated the population but enriched a new class of plutocrats and oligarchs. Russia’s efforts to integrate itself with the West met with an ambivalent, unwelcoming, and off-putting response.

In the immediate post-Cold War period, no one contested the global supremacy of the United States. In effect, Washington presided over a global sphere of influence that excluded only China, Iran, north Korea, and Russia in which it was able to act as it wished without regard for the UN Charter, international law, or other norms of international interaction it had earlier helped prescribe. Meanwhile, the liberalization and globalization of trade and investment brought new wealth to the world economy, including China and the global South.

But a combination of triumphalism and attention deficit diplomacy derived from resource-intensive “forever wars” and counterterrorism campaigns deprived the United States of any strategy for crafting a cooperative relationship with the newly reemerged Russian Federation. Instead, the traditional Western view of Russia as a latent enemy prevailed. Under pressure from Moscow’s Russophobic neighbors and their American diasporas, a military-industrial-congressional complex disoriented by enemy deprivation syndrome, diehard veterans of the Cold War, and force of habit, fear of Russia remained the guiding spirit of NATO.

Russian reactions (1994 – 2008)

As early as 1994, Russia began warning the United States that, if NATO enlargement extended to the Russian borders, Moscow would view this as evidence of hostility and mount a military response. But by 2004, every member state of the former Soviet-dominated Warsaw Pact had been inducted into NATO. In the Cold War, NATO had been a purely defensive alliance designed to counter Moscow in Europe. But in 1995, NATO began to take the offensive. It intervened in Bosnia and Herzegovina. In 1999, it launched a 78-day bombing campaign that wrested Kosovo from Serbia, a state traditionally associated with Russia. In 2001, NATO joined the United States in its twenty-year war to pacify faraway Afghanistan. And in 2011, it supported a regime change operation that threw Libya into anarchy. As NATO expanded toward Russia, Moscow came to see it as an increasingly active military threat.

In 2007, Russian President Vladimir Putin issued a strong warning against further NATO enlargement. But in 2008, under U.S. pressure, NATO offered membership to Georgia and Ukraine, both former constituent states of the Soviet Union bordering the Russian Federation. An emboldened Georgia then challenged Russian influence in minority regions on its Russian border. The result was the first European war of the 21st century, which ended in the Russian-aided secession of both South Ossetia and Abkhazia from Georgia and Russian establishment of suzerainty there.

Proxy war in the Donbas (2014 -?)

In 2014 a US-supported coup overthrew the elected but corrupt pro-Russian government of Ukraine. After the coup, the U.S. again pressed NATO to induct Ukraine. Ukrainian membership in NATO threatened, among other consequences, to deprive Russia of its centuries-old Black Sea naval base in Crimea. In a bloodless use of military measures short of war, Russia then took back Crimea, administrative control of which the Soviet Union had transferred from Russia to Ukraine in 1954.

Meanwhile, the new ultranationalist regime in Kyiv sought to make Ukrainian the sole language of official and interpersonal communication in public institutions throughout the country, ending the official use of Russian and other minority languages at both the national and regional levels. Soon thereafter, Russia conducted a referendum in Crimea, most of whose inhabitants — more than three-fourths of whom are native speakers of Russian – welcomed reincorporation into the Russian Federation. The Donbas oblasts of Donetsk and Lugansk, where Russian speakers are seventy percent or more of the population, then declared their autonomy from Ukraine, a decision that Russia endorsed.

Ukraine launched an offensive that recovered parts of the Donbas. Russia countered with military aid to the secessionists. Diplomatic efforts to restore linguistic and other elements of autonomy within a federalized Ukraine produced two never-implemented agreements (at Minsk). As the Donbas war proceeded amidst occasional ceasefires, Ukraine built a line of fortifications in the Donbas from which it daily bombarded the secessionists, whom Russia helped build formidable armies. The United States, Britain, and other NATO members made a major effort to retrain, reorganize, and re-equip the Ukrainian army. Russia simultaneously escalated its military support for the Donbas separatists.

War over NATO enlargement, Sino-American estrangement, and Sino-Russian entente

In late 2021, Russia demanded negotiations to rule out Ukrainian membership in NATO. The U.S. and NATO refused to discuss this. Russia massed troops on its border with Ukraine. The U.S. and NATO again rebuffed Moscow’s demand for talks about NATO enlargement. In early 2022, Russia recognized the independence of Donetsk and Lugansk, garrisoned them, and invaded Ukraine.

In response, the United States, joined by the EU, Britain, Australia, and a few other security partners, declared all-out economic war on Russia, cutting it off from the global dollar-based trading system, attempting to ban its energy exports, and seizing its dollar reserves, while initiating massive arms transfers and tactical intelligence support to Ukraine, which is now mired in a thousand-kilometer-wide war of attrition with Russia. The information war that accompanied the Western response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is the fiercest and most comprehensive in world history. With all sources of information other than those favoring Ukraine cut off, it is impossible to understand what is actually happening there. Whether a Western policy of support for proxy war in Ukraine can save it and restore peace in Europe is at best doubtful, but the economic war on Russia, its knock-on effects, the concomitant paroxysm in US-China relations, and the worldwide turn to protectionism driven by national security rather than economic concerns are together catalyzing the emergence of a very new pattern of international interactions.

The disorderly birth of another, yet unnamed world order (2022 -?)

The immediate U.S. war aims in Ukraine are to preserve Kyiv’s freedom to remain aligned with the U.S. and EU, if not now to join NATO. The longer-term U.S. strategic objective is avowedly “to isolate and weaken Russia.”

U.S. policies toward China parallel these objectives. Washington seeks to keep Taiwan in its sphere of influence and to isolate and weaken China in order to retain its regional and global economic and technological as well as politico-military supremacy. It should surprise no one that Beijing and Moscow have come to perceive a common interest in thwarting and countering U.S. policies aimed at subordinating them and retarding their growth in wealth and power.

U.S. policies of confrontation with Russia and China have unenthusiastic support from most NATO countries and Japan. But rising and resurgent powers, like Brazil, India, Indonesia, Iran, Mexico, Nigeria, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, and Turkey, oppose the effort to perpetuate the U.S. “unilateral moment” that they represent. With the notable exceptions of Australia, Britain, Japan, and south Korea, other major countries clearly prefer a multipolar, polycentric world order to one dominated by the United States or any other single power.

So far, the protectionist trade and technology policies the Trump administration launched against China in 2018 and the current economic and financial war on Russia are having pernicious results. China has accelerated its scientific, technological, and military advance. Far from collapsing, the Russian economy now has the second largest balance of payments surplus after China’s. Meanwhile, Europeans face recession, energy shortages, and other hardships. Both China and Russia are finding new markets for their goods and services. The war in Ukraine shows no sign of ending, and the probability of war in the Taiwan Strait is rising dramatically.

The shape of things to come

The world order that appears to be emerging is one in which:

- Sanctions-induced commodity and food shortages, breaking supply chains, and rearmament fuel persistent inflation.

- The fiscal burden of rising interest payments forces a turn to domestic pay-as-you-go policies and a choice between “guns and butter” that the U.S. has long evaded.

- The bloc formed by the United States, EU, Australia, Britain, and Japan to ostracize Russia and China is itself marginalized by the rest of the world, including its fastest growing economies and markets. Countries outside the US-led bloc refuse to choose between it and its designated adversaries, remain open for business with both, and reject the West’s imposition of end-use and retransfer restrictions on its exported products.

- The ability to mount planetwide responses to issues like climate change and pandemics is impaired. Every region is on its own and, in terms of its impact, the sum of the parts is less than the whole.

- The principal strength of the United States – its military prowess – proves irrelevant to most of the challenges in the emerging world order, which require economic responses that Washington cannot muster.

- Russia permanently abandons its three-century-long effort to integrate with Europe to seek an Asian identity through intensified relations with China and India.

- Turkey does the same, redefining itself as a West Asian and Islamic country rather than a European one and further attenuating its commitments to other members of NATO.

- Smaller countries resist affiliation with either the West or its designated adversaries.

- China’s “Belt and Road” initiative gradually extends Chinese economic influence throughout the Eurasian landmass and beyond in Southeast Asia and East Africa. Chinese political influence in the areas covered by the BRI gradually displaces that of the United States.

- NATO and other multinational alliances become less cohesive, with members gradually reducing or withdrawing their commitments to them.

- Germany, Japan, and other post-World War II dependencies of the United States rearm and develop more independent foreign policies.

- Latin America develops relations with China, India, Iran, Russia, Turkey, and other countries that increasingly undercut American hegemony in the Western Hemisphere.

- Africa is where most of the world’s industrial labor force comes to reside, and its economies become more connected to Brazil, China, India, Russia, and Turkey than to the EU or United States.

- Technology standards differ from region to region, and new technologies are often unavailable in regions beyond those that originated them.

- The internet evolves into regional and national zones, separated from each other by firewalls.

- Inexpensive Russian energy, metals, minerals, and other natural resources nourish economies in the so-called “global South” but are no longer reliably available at favorable prices to the U.S. and members of its anti-Russian coalition.

- U.S. sanctions give China and Russia a compelling incentive to form consortia with Iran and others to eliminate dependence on the United States for civilian, military, and dual-use products like passenger aircraft.

- The ability of the United States to finance its government and global power projection by issuing Treasury bonds is in increasing doubt, given the reputational damage of its confiscation of Iran’s, Venezuela’s, Russia’s, and Afghanistan’s dollar reserves.

- The rising risk from U.S. unilateral dollar-based sanctions causes ever more countries to price exports and imports in their own currencies, use swaps to pair their currency with those of their main trading partners, switch to hard currencies other than the dollar, institute point-of-sale digital cross-border currency exchanges, and create new units of account for transnational trade settlement. The “exorbitant privilege” that has underwritten U.S. global primacy unwinds.

- China, India, Russia, Arab oil producers, and other rising economic and financial powers respond to the incentives to build a separate financial world order that provides alternatives to the dollar-based SWIFT system and can destroy the effectiveness of U.S. sanctions as an instrument of foreign policy. They do so.

- Deglobalization generates multiple regional trade and investment regimes and divides global markets, from some of which specific great powers, like China, the EU, India, Russia, or the United States are excluded.

- Disputes over international transactions are handled bilaterally or by region-specific processes rather than by global dispute resolution mechanisms like those of the WTO.

- The world continues to rely on UN specialized agencies to address technical problems, but the UN Security Council and other international policy organizations, paralyzed by great power rivalries and disagreements, have diminished diplomatic utility.

- There are few, if any, new global – as opposed to regional — rule-setting treaties and arrangements. The worldwide regulatory regimes of the post-Cold War era atrophy.

- U.S. military supremacy erodes as regional forces strengthen themselves and new weapons systems and capabilities emerge in China, India, Japan, Korea, and Russia.

- Given the escalation risks of the US-NATO-Russia proxy war in Ukraine, the increasing likelihood of a Sino-American war over Taiwan, north Korea’s reliance on a nuclear deterrent for regime survival, the India-Pakistan nuclear standoff, and the incentive to acquire nuclear weapons that Israel’s nuclear arsenal provides to other countries in its region, the danger of nuclear war is now significantly greater than at any moment of the Cold War.

Conclusion

There is great dissatisfaction internationally with the now decaying “Pax Americana” of the late 20th century and a desire to see it replaced by a multipolar world order or orders in which different countries play leading roles in different sectors of world affairs. Current trends suggest that the kaleidoscope is once again rearranging international actors and their relationships in new patterns in which economic, financial, political, cultural, and military prowess is distributed regionally and functionally rather than centralized. But there has been little consideration so far of the likely consequences of an international system that entails much more complex interactions among states and peoples than before. If nothing else, this is a timely reminder of the old saying: ‘be careful what you wish for. You may just get it.’

To cope successfully with the challenges of a world with many competing centers, statecraft must take the long view, focusing on abiding interests rather than the passions of the moment. To manage a world in which rapid, unexpected change is the norm, diplomacy must be nimble rather than steadfast. And to be able to compete, countries must not only get their act together at home but employ all the instruments of statecraft – political, economic, financial, technological, and military – to shape the views and actions of their competitors to their advantage.